Scottish Art Pick: Alison Watt & Lessons From the Past - Esther

Looking back is the most important part of my practice. It has shaped who I am as a painter.

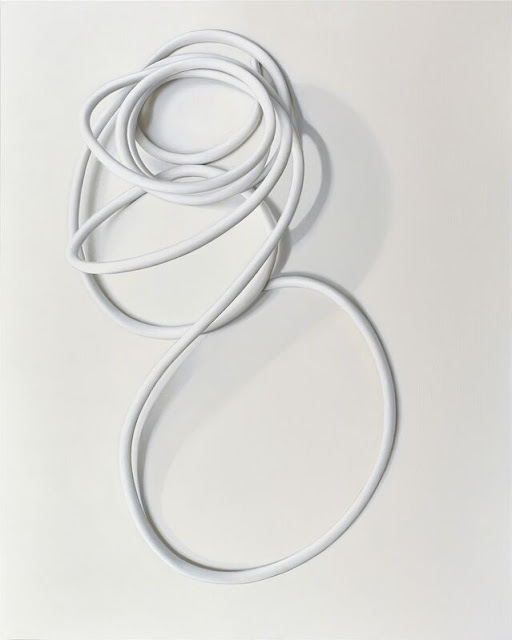

Flex (2017)

Recently I was lucky enough to see Alison Watt’s latest art exhibition, “A Portrait Without Likeness.” Housed in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery it is a collection of beautiful still life paintings in her typically realistic style. What makes this collection of images different from many others is the concept surrounding & informing it. More of that later.

Alison Watt makes much of the influence paintings of the past exert on her practice. One key influence took place early in life, being inspired to become a painter after viewing Madame Moissetier (1856) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres when she was seven. An important aspect of Ingres’s work she admired the most was his treatment of fabric & drapery.

At first, her interest was in portraiture & after attending Glasgow School of Art won the BP Portrait Award in 1987 for her self-portrait, also currently on show in the Scottish NPG. This resulted in offers of some high-profile commissions.

The portraits of the 1980s & ‘90s are distinctive. Some strike the viewer as allegorical, for instance Hunger & the Horse’s Head (1990).

Others do carry on the tradition of portrait painting throughout art history; they show people with an atmosphere of connection (or otherwise) in their own surroundings such as in The Artist & Her Sister (1986). We can see this is composed in Alison Watt’s flat (in St Vincent Crescent, Glasgow) from the canvases leaning against other objects behind the figures. This also continues the convention of artists portraying themselves in their occupation.

Still others echo the composition & story-telling nature of religious & early Renaissance artworks, for instance Cherries, Forbidden Fruit & Pear in a Landscape (1991). One thinks instantly of Botticelli.

Cupid After His Bath (1990) as an image coupled with the title shows a more playful approach to figure painting, whilst allowing Watt to showcase both the surroundings – the vast plaster fireplace, the type of which is common in older Glasgow properties & which are just as frequently painted over in white gloss emulsion - & her rendering of them. Then of course there are the cloths. A cushion so the model is comfortable & at least two or three sheets or drapes, not to mention the ones he’s wearing. Although the conventions of portrait painting are still observed & the figure is the main event, there seems to be an unnecessary amount of material…

Hood (2003)

Indeed within a few years Watt was focusing on the fabric itself & what it might imply. This was not a desertion of the human in her paintings, nor was she forsaking the figurative; rather she was exploring how the fabrics might represent the missing human figure.

The longer I look at drapery in painting, the more I seem to lose my connection with its original purpose. It begins to suggest other things to me & becomes a boundary between abstraction & figuration.

The first Alison Watt cloth painting I ever saw was probably Rivière (2000) in Aberdeen Art Gallery. Here we have an object that is basically plain white, yet like many other of her white fabric paintings there are in fact many colours in the composition.

The folds, knots, creases, wrinkles & pleats are meticulously rendered evoking the loin cloths of historical & religious paintings, the sheets that life drawing models are draped in, twisted up in or sitting on, the presence or absence of a person, someone’s clothing & parts of the human body such as genitalia. In Rivière there is an area that is also reminiscent of a scroll, which again reminds us of genre painting, Old Masters & literary figures.

2016’s 1708 appears takes the trompe l’oeil technique further – a plain, unfolded sheet of paper, with all the shadow, highlighting & smoothness you’d expect. Again, an object that at first glance appears to comprise little or no detail is found to have Because it is a painting & not the actual object, we are compelled to look into it further & observe these details Watt has picked out & directed us towards. These are paintings telling us to look. & then look further. & once you’ve done that, notice.

Because we attach so much meaning & significance to objects, they reflect us. They are a form of biography. As far as I’m concerned, the still life is a portrait without likeness.

Anne Bayne, Mrs Allan Ramsay (c. 1743) by Allan Ramsay

Alison Watt’s current show “A Portrait Without Likeness” focuses on the concept of the human absence & to me is the peak of this idea. The paintings are based on & inspired by the portraiture of Scottish master, Allan Ramsay (1713-1784). Two of Ramsay’s portraits are included, as are some of his beautiful drawn studies. What Watt has done is to take the objects out of his portraits (or at least found versions of these) & paint the objects themselves. As you walk round the collection, you are amazed at the light, realism & beauty, whilst being absorbed in her painting style.

Centofolia (2019)

Despite being aware of the concept it wasn’t until the final painting I became conscious of how very poignant it all was. She had taken the ribbon from around the neck or bonnet of Ramsay’s first wife Anne & painted that. The ribbon was still “here” after Anne had long gone. It was so cleverly hung that it made me see the whole collection afresh & I was truly moved.

Of this exhibition & her studies of Ramsay’s work, Alison Watt has said,

Looking into an artist’s archive is to view the struggle that takes place to make a work of art. A painting is a visual record of the inside of the artist’s mind. A painting is something that takes place over time; it is not static. To look at a work of art is to engage with an idea & that is not a one-sided activity. It is more of a conversation.

Alison Watt, we salute you.

Comments

Post a Comment