Art Genre: Art Deco - Esther

Perhaps one of the art genres most trapped in its own time is Art Deco. The term derived from arts décoratifs, a phrase first coined in 1858. When we think of Art Deco, we might picture The Great Gatsby, smooth, luxuriant surfaces, bold geometrics, sparkling skyscrapers, elegant curves, shiny cars & wealth; indeed it is partly characterised by the use of extravagant & lavish materials. Whereas the Arts & Crafts movement was said to have beautified & decorated as a social response to the grim functionality of life & objects produced during the Industrial Revolution, Art Deco was the decoration itself & can be seen as a reaction against more austere times. Art Deco articles & design quickly became less fashionable as the Great Depression hit & it was only retrospectively classed as a distinct style & movement in the 1960s. Broadly applied to buildings, furniture, ornaments, textiles, & jewellery Art Deco exploited the burgeoning resources, media & tools of the day but gave way to more utilitarian manufacturing when war approached, limiting available materials & what was expensive & could be seen as indulgent design. With hindsight, it is strange to think of reinforced concrete as a technological wonder particularly for use in such an extravagant art movement, but at the time, it was revolutionary & it helped put Deco on the art history timeline.

Buildings

Unlike many architectural advances & styles, there remain examples of Art Deco buildings in many UK towns & cities even today. They are likely to have been repurposed to meet the changing needs of the population of course, but thankfully the system of listing & therefore protecting of buildings ensures these structures remain largely intact in terms of the façades & some aspects of the interiors. An Art Deco building plonked in a city centre is usually eye-catching & distinctive, particularly if its more decorative aspects are close to pavement level or there is enough surrounding space to pick out the significant identifying lines & curves. For example, Aberdeen’s Northern Hotel (1938) may not be concrete & it may bear few hallmarks of the Secessionist movement that inspired Art Deco, but it is a classic Art Deco-style build. It seems to cruise along the street like a giant sea liner; it’s like the Flat Iron Building of Aberdeen & for this reason, can still be viewed largely as was originally meant. Constructed at a fork in the road, it would be a town planning nightmare to attempt to tamper with that area. More comprehensively tinkered with however is what was once the Capitol Cinema (1933) building on Aberdeen’s main thoroughfare, Union Street. It’s not the Chrysler Building (1930) but it’s pretty good.

Sculpture

Often Art Deco buildings were decorated with friezes or sculptures depicting ancient themes or epic figures. Paul Landowski’s Christ the Redeemer (1931) is arguably the most globally famous example. As with public sculptures, bronze was used for smaller, studio-made statuettes, which often depicted heroes or dancing women & used clean or curved lines. Almost every UK antique shop worth its salt will have one or two Art Deco figurines tucked away in its shelves. Demétre Chiparus’s Tanara (c.1925) showcases the influence Paris-based Ballet Russes costumes had on Art Deco artists.

Painting

Tamara de Łempicka’s paintings clearly show the deep influence Cubism had on Art Deco. She honed Cubist principles to develop a highly recognisable technique, which in many ways embodies the overall style of the genre. Portrait of a Man or Mr Taeusz de Łempicka (1928) evokes her characteristic style of portraiture as well as portraying him in a “modern” setting, surrounded by what was contemporary architecture & skyscrapers. In the spirit of the arts décoratifs as opposed to fine art in itself, murals were widely popular particularly in the USA during the 1920s & 30s, such as Reginald Marsh’s 1936 Sorting the Mail (for the William Jefferson Cointon Federal Building).

Fashion

Also strongly under the influence of Cubism was Sonia Delaunay, who was one of the first to incorporate geometric patterning into the world of fashion design. Her works such as Beach Wear Designs (1928) & Dresses (1923) capture a visual association with The Jazz Age. Romain de Tirtoff, better known as Erté has translated well into contemporary perceptions of Art Deco. His designs – art pieces in themselves – such as Opera Coat (1916), Chapeau (1923) & Pearls (1983!) embody the sumptuous & glamorous fashion fantasies of the time. He continued working well into his 90s & nowadays his work is frequently appropriated for merchandise such as calendars & notebooks – as it turns out, his is a truly decorative art.

Jewellery

The overarching Art Deco style & motifs are prevalent in jewellery design & preference even today. It is unlikely many of us have any René Lalique originals lying about that we don’t know about. Nevertheless we can clearly recognise his enduring influence when viewing his Molded Glass Pendants on Silk Cords from 1925-30 in much modern fashion embellishment & jewellery. His Necklace (1897-99) & Corsage Ornament (c.1903-5) are more reminiscent of their time, the brooch with its dragonfly motif & use of enamel.

In spite of many of his contemporaries turning away from an Industrial style, Jean Despres preferred to celebrate it & further incorporate Cubist ideas into his jewellery design such as in these Brooches of 1933.

Advertising

With industrialisation came motors & by the Art Deco period, these were becoming more sophisticated & perceived as elegant things of beauty. Here Gerold Hunziker’s Bugatti (1932) advert verges on abstraction & focuses on depicting the car’s movement & the clean lines attractive to discerning buyers. Not to be confused - nor mixed - with driving of course, is alcohol. Back then, graphic artists were trying to get us drunk in inventive, stylish & beautiful ways. Little has changed in that regard & even today & companies continue to use the Deco style in adverts. Delval’s Fap’Anis (c.1925?) combines glamour, colour & a lovely sunny beach to encourage profligate wine-drinking.

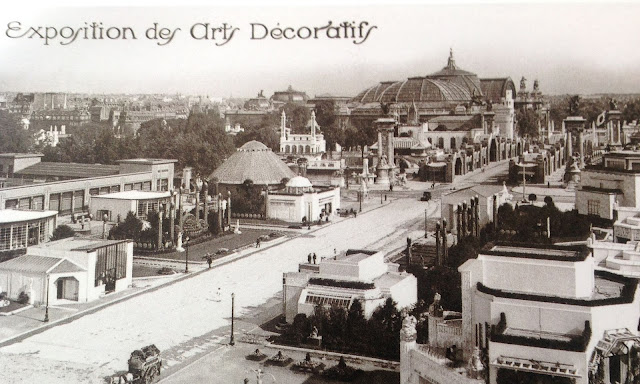

Finally here’s a poster from the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the event that started it all off; the show which sought to display & promote the day’s arts décoratifs & birthed Art Deco as we know it.

Another interesting and instructive session. Art Deco is one of those “I think I know it when I see it” styles, but I had no idea its roots went back to an 1858 coinage. My vague knowledge had me associating it with a general cultural swell from the hopeful turn of the 19th and into the 20th century, with rising innovations in urban life, public health, and a man-made environment where science and technology were showing us the way to a brighter future for all. The horrors of technological advances in warfare dampened some of this during The Great War, but it seemed to roll on through the twenties, vaguely sputtering out during the Great Depression – though still echoing in the public works projects of FDR’s administration, and similar efforts elsewhere.

ReplyDeleteA fair chunk of my early professional work in materials science (an area I more or less stumbled into as I was nearing my thirties) involved innovations in concrete – a much more interestingly dynamic area than most people realize. Most people don’t know that unless it’s been interfered with – damaged or obstructed at a molecular/chemical level -- that in the presence of some moisture concrete becomes stronger, year after year. Decades, even a century or more later. It’s to a tiny, incremental degree once one’s past the first 28 days or so, but it’s there.

The proportioning of ingredients in the mix is critical – perhaps the biggest one to start being making sure there’s juuuuust enough water in the initial mix. Once it’s poured and begins to set, then it can have as much water as is around, but when it’s still in a plastic, flowable, placeable form, it needs to have as little water as possible. Add more water early, to get it to flow and be easier to place, and you’ll pay for it with weak, dusty-surfaced, concrete. The careful addition of ultra-fine particles like silica fume have helped modern, specialty mixes achieve amazing strengths, and have allowed innovations in modular construction. If anything, I’m surprised we haven’t seen more innovation in the past 30 years – but, then again, the continued lack of a much-needed public works administration’s been a problem on so many levels. Greed and short-sightedness have damaged us to our core, with the neglect of both infrastructure and the general human spirit, both of which need so much more tending than they've received.

Apologies for the digression. I can only say that I restrained myself to keep the above contained.

Thanks again for the continued enlightenment, Esther.