Scottish Art Pick: James McBey & the Power of Perseverance - Esther

If ever an artist changed the course of his own life through sheer will, determination, skill & hard work, James McBey (1883-1959) did. From extremely humble beginnings on the Aberdeenshire coast, his early life was difficult & poor. Initially, he seems to have had little encouragement - & little training - & his sense of purpose & interest in art were what took him further. His was a tale like many others born into poverty & difficult circumstances, with no apparent opportunity or help who manage through their own willpower, discipline & single-mindedness to escape the path originally set for them.

It’s lucky we have his autobiography to tell us about his first twenty-eight years of life because his later art & lifestyle give away very little of what he endured. A keen diarist, his writing is remarkably matter of fact in places & in others surprisingly reflective, for instance on discovering his mother hanged at her own hand in the cellar. I say “surprisingly” given the company he later kept & the way he portrays himself – confident, a man of the world, assured - in his painting. He also speaks humbly about how others positively perceived his work. In NE Scotland (or Scotland generally), it’s frowned upon to be pleased with yourself or have ideas above your station. Nor is it even acceptable to show off on behalf of members of your own family…

Benicasim, 1911

He details his experimentation & development of methods in the complex medium of etching. He describes acquiring the copper, handling the wax & needle as well as the difficulties of keeping the delicate wax layer unscratched & the problems he had finding & storing a press.

(See the process: https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/printmaking/etching).

All this he discovered entirely by reading about the process in the library & more significantly, through his own trial & error. It’s said that he always printed his own etchings (early on using a mangle as a press), to the tune of around 10,000 prints by 1928. If you see or discover a McBey engraving until then, you can be sure he made that copy – pardon the pun - from scratch. His etchings were highly prized in the post-war period, realising huge sums.

The Long Patrol, the Wadi, 1920

McBey seemed to inherit his mother’s poor eyesight, which thankfully ruled him out for military duty during WWI. After some time in France in his position as second lieutenant, he was eventually engaged as a war artist to the Egyptian Expeditionary Force; the government never used much of the resultant work however. One of his best-known & effective works is of T.E. Lawrence in 1918 & he was subsequently commissioned to undertake other high-profile portraits. Pleasingly he was known to hold a gentle grudge. On being turned down for membership of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers & Engravers & for exhibiting with the Royal Academy & later offered membership, he politely refused. He would never try to work within such societies again.

He married American Marguerite (Loeb) McBey in 1931 & they moved to Tangier. He became a US citizen in 1942, moving back to Tangier after the war. Marguerite – herself an artist & bookbinder - proved pivotal in carefully curating his legacy & distributing his works to various significant galleries after his death. Her bequest to Aberdeen Art Gallery resulted in a library named after him. We have much to thank her for.

It’s fascinating to see how McBey handled colour when he moved onto painting (around 1912) & his watercolours have a fresh, characteristic look about them. As shy as he might have been at points about showing his work to others, he appears to have been less fearful of trying new media.

He travelled widely, partly through the army & seems to have sketched & painted wherever he went. When McBey finally got to see Rembrandt’s etchings, they greatly influenced his own work & he described seeing Whistler’s work:

“What fascinated me most of all was the technique…Although the brushwork was vigorous, the finished surface had a beautiful enamel-like quality which by comparison made the work of other artists appear rough, forced, even haphazard.”

He admired “the softened edges and the restrained colour.”

Perhaps the best description of McBey’s own working methods is by one Martin Hardie who worked for the V&A & accompanied him on a visit to Venice:

“Every morning…in the autumn of 1925, he was out at 5am to see whether the sun was rising in mist or cloud, or in a sky of blue. He began at dawn…making pen & ink notes of figures…or buildings & their reflections; at night he would be out again in his gondola, working on a copper plate by the light of three tallow candles in an old tin! Never has anyone been less dependent on the orthodox paraphernalia of his craft.”

We can see he was intensely disciplined & self-sufficient, keen to study his craft & learning well. He made things happen for himself & relied on no-one. Although this is hard, it’s also very liberating.

It’s very moving to think of him seeing for the first time some of the paintings – or indeed any paintings - I know well that still hang in Aberdeen Art Gallery & walking the route to his job in the bank from the flat he shared with his mother & grandmother. These buildings still exist (the flat has a commemorative plaque to mark his residence & there’s another in London), almost all of the buildings on that route remain standing & he was viewing much of what anyone in Aberdeen can see today.

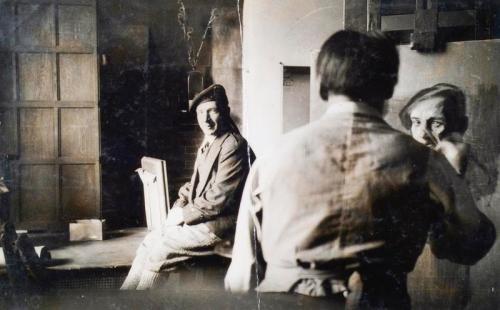

Self Portrait, 1952

James McBey willed himself into being who he became. In a sense the reverse is also true; even in death, he went down fighting. It’s somehow appropriate that in his final (possibly only) illness, he reverted to the retrograde ways of his upbringing that determined one ought to exercise to get well & chopped wood to try to cure himself rather than seek treatment or rest. Despite dying of pneumonia in Morocco, in my mind’s eye I can’t help picturing this scene against the wet, grey mists of Newburgh, Aberdeenshire.

James McBey, we salute you.

Great writing, I've been in the McBey room many times but never knew his (rather splendid) story.

ReplyDeleteThanks Pete - I love that there are so many photos of him too. When you match them with that story...

Delete