On not reading The Torah like a book -- Garbo

When the Jewish New Year started during the third week of September, as is my custom, I set a new spiritual study goal. For 2020/2021, I decided to read each Torah portion during its assigned week. There were parts of the Torah I knew well, and other parts I knew I'd never read. I thought "I'll have a better foundation for my understanding. And hey, a little discipline plus goal-setting? Good idea!"

The portions, as you may know, are the traditional way of dividing the five books of Moses to be read, in the temple and at home, over a year's time. The first portion goes from the first verse of the first chapter of Genesis to the sixth chapter, eighth verse. The second portion picks up at the ninth verse of Chapter 6, and goes till the end of the eleventh chapter. Genesis has twelve portions in it, and then the Parshat (portion) arrangement moves into Exodus, then Leviticus, Numbers, and finally Deuteronomy.

So I printed out a handy-dandy chart I found on the internet, which had the readings week by week. Sometime before the sun fell below the horizon on Friday evening of the first week of the New Year, I sat down to read the Jewish Bible. Backwards, of course, because the sacred texts are read from right to left, just as the lines of Hebrew characters are read starting from the right. So what would be the back cover of a secular book is the front cover of religious material translated from Hebrew.

Over the next few weeks I dutifully made my way through the tales of Creation, Adam and Eve and their children (including that oft-forgotten son, Seth) and worked my way along to the story of Noah, the flood, and what happened after the dove came back with the olive branch in its beak.

If you've forgotten some of the details: After the waters recede, Noah and his family settle down on a little farm with a vineyard and there's homemade wine to be made. One night Noah has too much wine and passes out naked in his tent. His son Ham sees his drunk nekkid father, feels shame, and goes to tell his brothers. The brothers make a plan, and they back into the tent with a shawl spread out over their shoulders between them and drope it over their father's sleeping form. Noah wakes up, finds the shawl draped over him, finds out that it was Ham's idea and curses him -- and his offspring for good measure -- and tells him they will all be servants to others for all time. And for good measure Noah makes one of the two shawl-carrying sons the servant of the other's family. I was moving along through the verses of Genesis and then I was was all like, screeeeeech, stop. Close the cover and think.

It's not like I didn't know the stories; I've known them since childhood. But the non-stop murder, sexual assault, and patriarchal temper tantrums that led to casting people out of Paradise for disobeying once -- it was wearing me down. And now the one guy God chose to save from drowning the Earth is flinging around random curses like pieces of stale Laffy Taffy from the bottom of the Halloween candy bowl.

I said to my spouse, "If this was a regular book, fiction or non-fiction, I wouldn't have even kept reading this far." And yet I'd committed to a year's study of the Torah.

So while it's been a learning experience already, I've decided that I need to re-frame. While I own The Torah: A Modern Commentary, which has maps and a glossary andtreference notes as the bottoms of the pages, a few marginal explanations are not enough. I find that I need to put the Torah into its historical setting and view it at more of a distance. I've been treating it like some kind of incest-ridden tale of visions and community infighting and general mayhem, or like a badly-drected indie film with a jumpy story line filled with re-tellings and backtracking. I need much more context to see what the Torah really is.

At one time I knew more about how the Biblical texts were assembled and put in order, and how the stories in them matched up -- or didn't -- with recorded human history. But it's been a while since I read up on all that. Also there is a lot to know; like a year's worth of study, just to get a basic grasp on it.

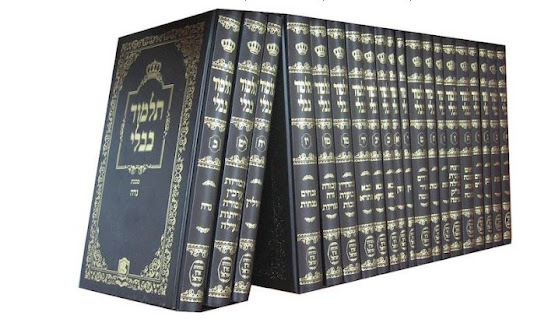

I've begun the process by mentally sorting out canonical texts. I'll share a little of that now: The Talmud and the Mishnah are ancient collections of writings by rabbis, plus recorded oral teachings. Those two books are where religious leaders find all the laws and rules and accepted history. And then there is the concept of the midrash, which is a study and/or explanation and/or expansion of material in the Talmud. Like it needs expansion, ha ha. The Talmud is a multi-volume deal.

Whereas the Mishnah is a skimpy 844 pages of small type.

In this series of blog posts, my focus is on just the Torah, the first part of the Tanakh, which some people call the Hebrew Bible. A lot of the writings overlap with the part of the Christian Bible known as the Old Testament, but it's not an exact match.

The Tanakh has three parts, and "Tanakh" is a created word built from the first letters of the names of the three parts. It's like NaNoWriMo for National Novel Writing Month. Biblical Hebrew uses consonants plus special indicators for the vowel sounds, and so "Tanakh" is built from the consonants T - N - K which stand for Torah, Nevi'im, and Ketuvim.

Nevi'im means Prophets, and they are grouped as Former (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings), Latter (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel), and Minor (there are a dozen of those). Ketuvim means Writings, and that's the part of the Tanakh that starts with Psalms and Proverbs and the story of Job, followed by the special holiday stories called Megillim, which are read aloud. The best-known of these is the Megilla which celebratesQueen Esther and her triumph over the villainous Haman. The Writings contain many other books, including the stories of Ruth and Daniel, and the books Chronicles and Ecclesiastes. The Nevi'in is also the source for Haftarah, which is a collection of written material which accompanies the reading of the Torah during Sabbath services.

You can see how Jewish scholars keep so busy -- that is a large accumulation of preserved writing. I'd never be able to even skim all that in a year's time. So I'll set aside the Prophets and the Writings, and work with the first part of the Tanakh, The Torah. In this series of posts, I'll describe how the process of seeing the texts set into a frame of history and culture is going.

In a future post: considering the Torah by itself

Garbo

Comments

Post a Comment